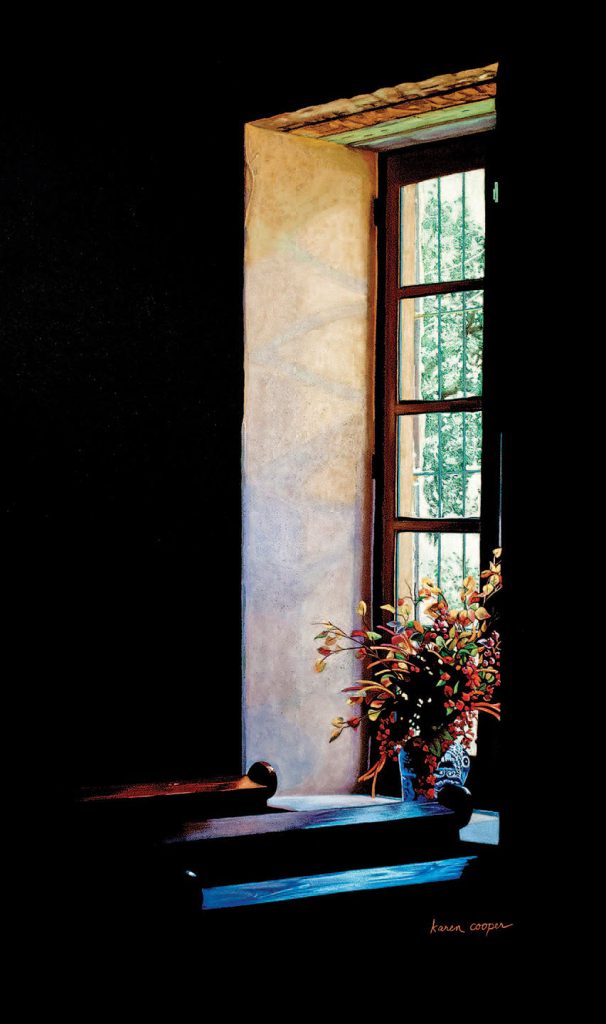

Karen Cooper’s award-winning paintings take the eye in an unexpected direction as well: from areas of solid form and vibrant color into deep black shadow where parts of the image may be clearly “seen” — but are not really there.

The farther east Karen Cooper moved over the years, the more she found herself expressing the West in her art. She started off in Northern California and doesn’t expect to go any farther east than Kerrville, Texas, where she’s lived since 2012. But each move — and a 10-year stint in Santa Fe — settled her deeper into the history and culture of the West. Her award-winning paintings take the eye in an unexpected direction as well: from areas of solid form and vibrant color into deep black shadow where parts of the image may be clearly “seen” — but are not really there.

In her Kerrville studio on an escarpment high above the Guadalupe River, Cooper looks through some of the countless photographs she has taken: images of iconic Texas landmarks like the Alamo, or ranch life, or ground-level rodeo action captured through a camera-slit in the wall of a sub-ground arena bunker at Cheyenne Frontier Days. She selects an especially inspiring image and produces a meticulously detailed drawing, leaving nothing out and ensuring accuracy when the eye later connects the parts that are separated by black.

She transfers the drawing to black pastel paper, but before she does she erases all the drawing lines where the image will disappear into shadow. Cooper checks the careful balance of light and dark, occasionally painting part of the image that is in the shadows to allow the composition to convey all the details that it needs to be complete. Then, building up rich color with as many as 10 layers of soft pastel, the artist deftly renders the areas struck by sunlight, leaving the untouched paper to suggest what the shadows hide. She has had collectors insist they can see the parts of the image deep in shadow. She smiles and shakes her head. That’s the magic of visual perception, she says: Our brains supply the information our eyes don’t actually see.

Click on the image above to view the slideshow.

Understanding negative space has been integral to Cooper’s creative approach since she began drawing on scratchboard at age 15. As an exchange student at an experimental art school in Sweden, she studied copper-plate etching and oil painting and was introduced to textile art. She earned a bachelor’s degree in textiles from San Francisco State University and traveled to Guatemala to study with indigenous weavers, an experience that enhanced her sense of color. Later, an associate’s degree in architectural design and a nine-year stint in architectural hand-rendering honed her drawing skills and further developed her insight into patterns of shadow and light.

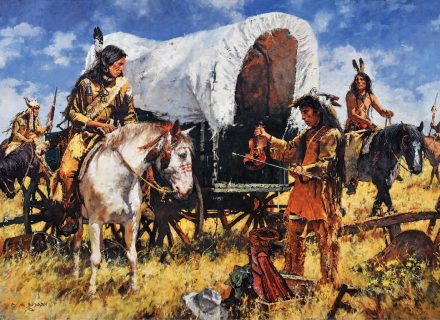

Although it took settling in Texas to move fully into Western subjects, Cooper has a personal connection with the history of the West: Famed outlaws Frank and Jesse James were her great-grandmother’s second cousins, and a more direct ancestor was a scout, along with Kit Carson, for explorer John C. Frémont on expeditions into pre-Gold Rush California. Cooper is a fifth-generation native of the state. That genealogy has instilled in her a sense of what she calls pioneer ethics. “It’s pride in family and God and country and was very important,” she says. “I try to show it in my work, in history-related subjects as well as the modern West.”

Karen Cooper is the featured artist for the month of March at the Museum of Western Art in Kerrville, Texas, and will be in the museum’s exhibition and sale, The Party, opening September 7 and running through the end of October. She is represented by Studio Gallery in Waco, Texas.

Photography: (all images) Courtesy Karen Cooper

From the April 2019 issue.