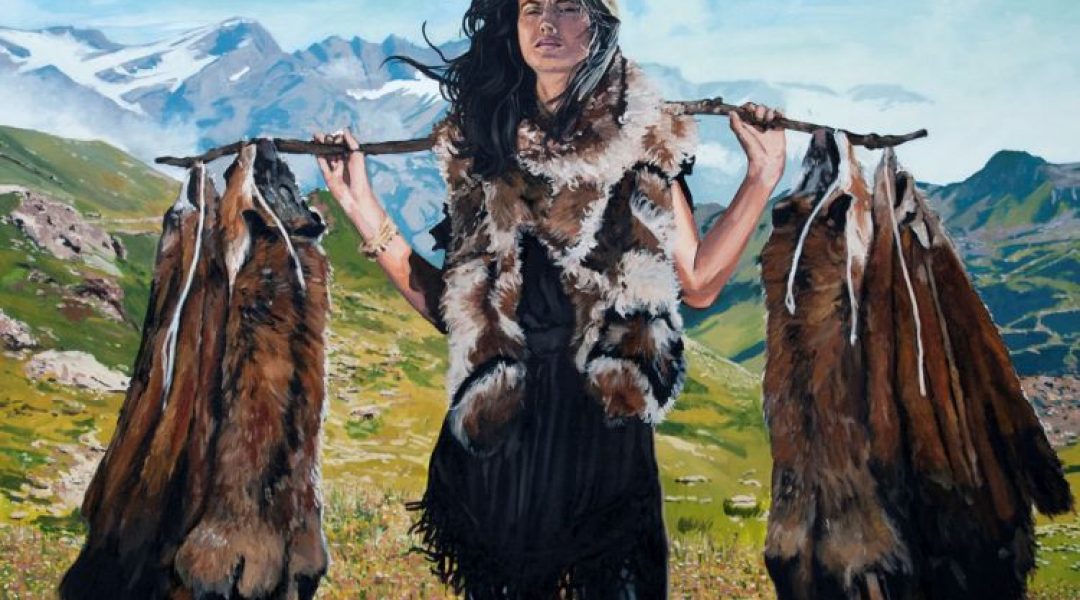

Tracy Stuckey’s riveting paintings are at once whimsical and unsettling. His fascination with the “Ralphlaurenization” of the West informs his sly, satirical paintings of the mythic American landscape.

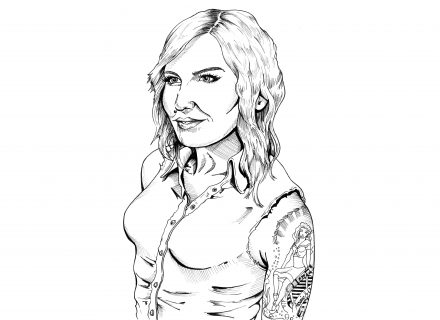

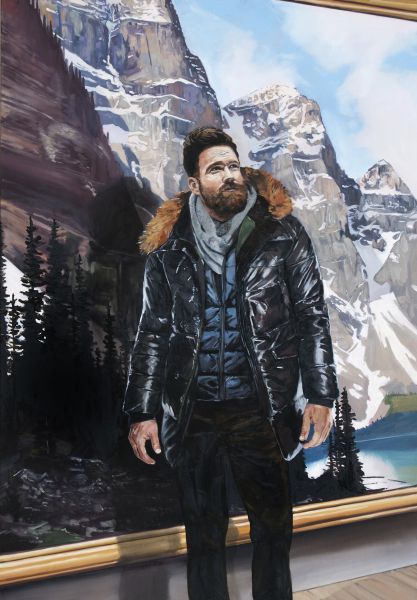

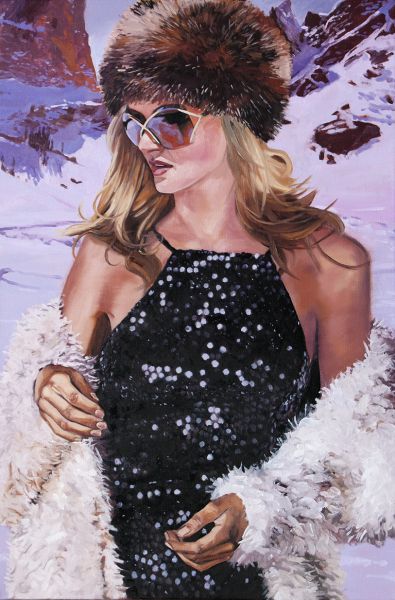

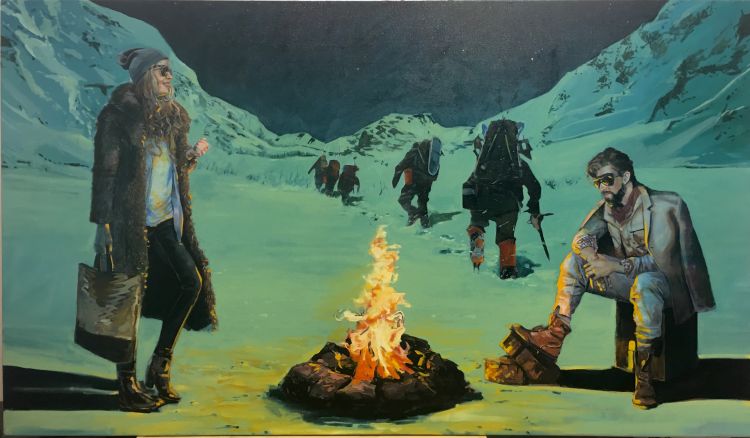

His large-scale oils — mashups of the romantic longings, pop culture, and images of a West that never was but nonetheless cemented our Western identity — draw inspiration from a century of dime novels, Wild West shows, and silent films, but with a twist. Tracy Stuckey borrows from classic cowboy iconography, Western film and cinema, advertising, and quirky news stories and then pastes modern characters into fanciful situations where bikini-clad beauties show up on cattle drives.

“I find images in magazines or I take my own photographs and piece them together in digital collages; then I paint,” Stuckey says. It’s an illustrator’s technique Norman Rockwell and Thomas Eakins used, he explains, but Stuckey diverges from their idealized and romanticized realism, exploring instead an urban-wild interface where wildfires rage beyond sparkling turquoise swimming pools and coyotes attack poodles. His visual narratives contain both 19th-century references and allusions to Western cinema and film; and you are as likely to find a nod to Jane Jetson of 1960s cartoon fame and the motel room from No Country for Old Men as you are a gunslinger with his Buick Skylark and a James Dean-like figure shot with arrows against fence rails in a Red Rock Country variation on the martyred Saint Sebastian.

Stuckey’s glossily attractive characters strike poses like models or actors but don’t engage emotionally with one another. “They’re wearing costumes and playing their own roles, their own archetypes” in their own Western fantasies, he says.

The artist grew up in an archetypal American atmosphere: the car and beach culture of Florida. His father built and raced cars. As a teen, Stuckey briefly tried painting his dad’s cars with an airbrush. “But I was into surfing,” he says. “I aspired to paint murals on surf shop walls.” After studying painting and fine arts at Florida State University, he went west for his MFA at The University of New Mexico with his own romantic notions in tow. “My vision of the West came from film and television, from music, fashion, and popular culture. The kind of ‘fakelore,’ that inspired stories of Pecos Bill and the Townes Van Zandt ballad ‘Pancho and Lefty.’ ”

Today, Stuckey lives in Fort Collins, Colorado, with his wife and two young children and teaches art at Colorado State University. “In New Mexico, I painted light and warmth, but here in the Intermountain West, it’s mountains and mining history and cold and buffalo hunting and bears.”

His current show is inspired by Frederic Remington nocturnes. Just as Stuckey would 150 years later, Remington painted what the Wild West meant, not its reality: “The night is never that color; the moon is never that bright,” he says. Stuckey also plays with cinematic lighting techniques from the classic 1956 John Wayne-John Ford film The Searchers, shot during the day with a night filter. “The light in the night scenes is wrong,” Stuckey remarks. “The shadows are too long.”

Yet, somehow, those images are ingrained in our psyches as the true West. And there’s something of that in Stuckey. So what if a bison reclines poolside as a cowboy cutout of a dude strides self-consciously on his mountain-modern deck? Stuckey’s is a surreal, yet recognizable, West, awash with familiar touchstones but dangerously wild.

The Color of Night is on view October 19 – November 24, at Visions West Contemporary in Denver.

From the October 2018 issue. Cover image is of The Fur Trapper.