The Oscar-nominated actor co-stars with Joaquin Phoenix in director Jacques Audiard’s audaciously offbeat western.

They are notorious hired killers — assassins, really — who sustain their fearsome reputation by shooting first, and last, and never bothering much about asking questions afterwards. Still, there is something, if not quite lovable, then darkly comical about the title characters in The Sisters Brothers, the critically acclaimed and uniquely eccentric western that, after impressing audiences on the international festival circuit, is rolling out in wide North American release this weekend.

But be forewarned: This is not your grandfather’s shoot-‘em-up. On the other hand, your father might recognize it as a blood relation to such revisionist westerns of the 1970s as The Hired Hand, McCabe & Mrs. Miller, The Culpepper Cattle Company and The Great Northfield Minnesota Raid.

The Sisters Brothers is the first English-language feature from French filmmaker Jacques Audiard (A Prophet, Rust and Bone), who provides a curious outsider’s point of view for what might sound in synopsis like a typical sagebrush saga, and transforms it — with more than a little help from a terrific cast and co-screenwriter Thomas Bidegain (Les Cowboys) — into something every bit as unpredictable (and, very often, unsettling) as the picaresque Patrick deWitt novel on which it’s based. As critic Inkoo Kang wrote for the Slate website: “Unlike many of his European compatriots, Audiard, a filmmaker long attuned to racial and economic issues, is more than convincing in his depiction of the American West in his English-language debut, its perceptive and compassionate details finding harmony with the script’s genre elements. But it’s the central fraternal relationship that makes this adaptation of [deWitt’s novel] a near-masterpiece — a simmering chase movie that gradually heats up to a searing family drama that wonders how to care for a loved one that’s impossible to live with.”

Charlie Sisters (Joaquin Phoenix), a hard-drinking, itchy-trigger-fingered sociopath who takes unseemly delight in ending lives, and Eli Sisters (John C. Reilly), his appreciably less mercurial but equally lethal older brother, are employed by the enigmatically powerful Commodore (Rutger Hauer, who doesn’t speak a word but gets his points across) as enforcers, executioners and, on rare occasions, interrogators during the California Gold Rush era. Their latest assignment: Find an idealist young chemist, Hermann Kermit Warm (Riz Amed), who has concocted a formula for finding gold, and extract from him the secrets of his scientific breakthrough by any means necessary. In this task, the siblings are assisted by John Morris (Jake Gyllenhaal), a rather more refined advance scout who’s supposed to locate, befriend and delay Warm until the Sisters Brothers can catch up.

Not surprisingly, nothing goes according to plan. Very surprisingly, the Sisters Brothers, who seldom aim to please, wind up getting a shot at redemption. Still, the question remains: After experiencing the childhood traumas that shaped them into killers — their shared past is only gradually revealed as the movie progresses — will it be at all possible for them to choose another path? A path, not incidentally, that they can take only while hotly pursued by the kind of men they used to be?

“One of the things that gradually sinks in as you watch The Sisters Brothers,” critic Justin Chang noted in his Los Angeles Times review, “is just how damn likable everyone in it is, the spirit of optimism that prevails even among men who have suffered more than their fair share of past persecution and abuse. OK, so Charlie’s a wreck, but there’s still hope for him and especially for Eli, who carries a torch for a woman back home and can still bring himself to weep over a dead horse. All he wants is to finish the proverbial one last job and get out of the game for good.

“The deep kinship that forms between Hermann and John,” Chang added, “is predicated on an even higher-minded desire. After striking it rich, they want to establish their own community in Dallas where peaceable, like-minded men can live in accordance with truly democratic principles. It may be a pipe dream, but it’s a beautiful one.”

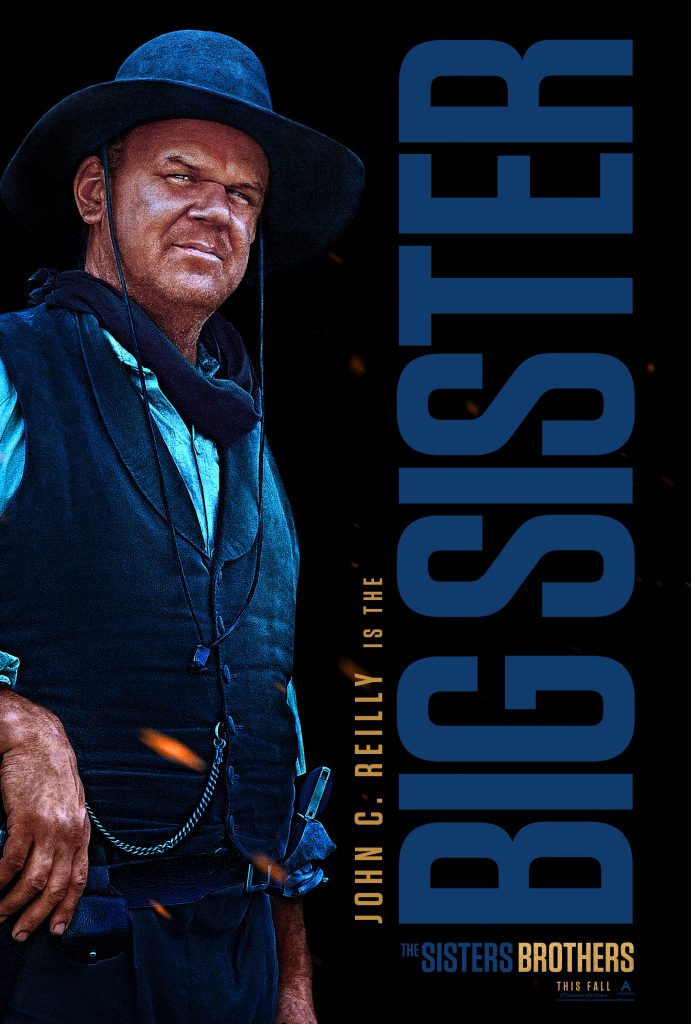

For John C. Reilly, the celebrated actor whose lengthy resume includes everything from broad comedy (Talladega Nights: The Ballad of Ricky Bobby, Step Brothers) to ensemble dramas (Magnolia, Boogie Nights) to a based-on-a-Broadway-hit musical (Chicago, which netted him an Academy Award nomination as Best Supporting Actor), The Sisters Brothers was a dream project. But as producer and star of that project, he had to wait a while before he could see the dream turn into reality. We caught up with Reilly shortly after The Sisters Brothers had its North American premiere at the Toronto International Film Festival. Here are some highlights from our conversation.

Cowboys & Indians: We understand that The Sisters Brothers was a labor of love for you — but that the seed for it was planted by your wife, producer Alison Dickey?

John C. Reilly: Yeah, we were working on a movie together called Terri, this independent film that was directed by Azazel Jacobs. And Azazel knew Patrick deWitt, and Patrick had written the script for Terri. At the end of that project, my wife asked Patrick if he had any other writing. He had this manuscript for The Sisters Brothers — and he slipped it to us before it even went to a publisher. And we fell in love with it. And I especially loved the character of Eli. That began the odyssey. It’s the first and only time I’ve ever done that, bought the rights to something. It’s just that this book, it really spoke to us all as soon as we read it. And we knew that it would make a great film. I can’t believe we are where we are, to tell you the truth. It’s hard to believe that it happened in seven years. There’s some luck behind the number seven, as it turns out.

C&I: What made you keep believing in the project over the years?

Reilly: What kept us going was, each step of the way, someone joined us in this venture. First we got our friend Mike De Luca to come on as a producer with me and Alison. Then we met Jacques Audiard, and his whole team signed on, and he started doing rewrites of the script. And each step of the way, we’d get some more wind in our sails. And the next thing you know, we were at the starting line to make the movie. It was not easy and it took a long time, but it really did come together beautifully in the end.

C&I: Why did you think Jacques Audiard would be a perfect fit for The Sisters Brothers?

Reilly: Jacques is just one of the greatest filmmakers out there. And we were shooting for someone at the top of their game — someone who’d take this material, and transcend the material almost. Bring something of their own personal point of view to the film, and someone that was gonna have the confidence and the technical ability to do that. Jacques was definitely someone that we’ve just been in awe of for so long. My wife especially has been watching every one of his films as they came out. And then we quickly realized, if we wanted to avoid a lot of the clichés that come with westerns, if we wanted to avoid repeating ourselves in terms of the western genre, it would be really good to have someone with an outside perspective. I think Jacques is the only French guy to ever direct a western outside of France. And he definitely brings that objective point of view to it.

We Americans have a lot of baggage culturally regarding how the country was founded, and a lot of it is based on these wonderful, famous westerns that we have in our culture. But someone like Jacques comes at it from a whole other point of view and it’s a pretty fresh take. He's looking at it as a period piece as opposed to a western. It just happens to be 1851 in the Pacific Northwest and we proceed from there. It’s funny, because when you hear the term “revisionist western,” well, what exactly is being revised? Other movies’ version of the West, or the historical record, or what? I don't think Jacques set out to revise anything. I think he just set out to tell the truth about some characters that were alive at a certain time in the world’s history.

C&I: The central relationship between your character and Joaquin Phoenix’s character — Eli and Charlie — creates a fascinating dynamic throughout The Sisters Brothers. Charlie is the more hot-headed and capriciously violent of the pair, yet he’s also the one who more or less takes charge of their murderous assignments. He’s the one who appears to truly enjoy their work as hired killers, and is eager to sustain their reputation as very bad men. But because he is such a heavy drinker, and is so reckless, Eli actually serves as his protector to a large degree.

Reilly: Yeah, they’re both damaged goods. In that way, they’re different than your usual bad hombres in westerns. You understand that they come from this really traumatic place when they were children. And it makes you realize that even though they do this terrible thing for a living, in some ways, it’s not entirely their doing. Because they were pressed into this violent life so early, before they had developed empathy and those kinds of things, you end up having some sympathy for them by the end of their journey.

C&I: How much time did you spend on horseback before making The Sisters Brothers?

Reilly: I actually did another movie with one of the writers of this movie, Thomas Bidegain, a French film called Les Cowboys, and I did some horseback riding in that one. And there have been some other films where I’ve ridden horses. But most of the riding I’ve done up to this has been just recreational. That’s really like riding on top of a horse as opposed to riding the horse. But I got really close with the horse on this one, a Spanish horse named Pollito. We became really close. He was really smart and we took good care of each other. I was really sad to say goodbye to him. He retired at the end of our film.

C&I: So he was a professional movie horse?

Reilly: Yeah, you’ve got to use professional movie horses when you do movies with horses, because there’s a lot for horses to get used to on a set. You can’t just expect any old horse to be able to deal with a camera and the noises and stuff that go around on the set. This guy — Pollito was his name, meaning “little chicken.” And I really loved that guy. I used to go visit him on the weekends and bring apples and stuff, because I wanted him to be my friend. I wanted him to remember me, because your safety is so tied into your relationship with those animals. They’re really deep once you get to know them. They’re almost telepathic.

C&I: How did you bond with Joaquin Phoenix? Did you bring him apples, too?

Reilly: [Laughs] Yeah, I did bring him apples. But he refuses any gift. Joaquin is not a person who’s easy to buy gifts for. My thing with Joaquin was, he just doesn’t like to talk about stuff too much. He doesn't want to over-analyze things. He’d rather just experience it with you. He’s really good at following the moment, and just seeing what happens. He’s a great improviser in that way. So we just hung out. We just lived together for a period of time. We cooked for each other, we’d ride horses together, go on long walks. And that’s when we started to open up with each other a bit more. It was a lot of just being each other’s company. Similar to the way the brothers are in the movie.