Not 10 miles from the famous western film location of Lone Pine, California, photographer Ansel Adams documented a very different chapter of western history at the Manzanar Japanese internment camp.

When C&I interviewed photographer Jody Miller about her career for our February/March 2018 issue, we were fascinated by her stories about Ansel Adams. She’d studied with the master and had firsthand information about his work and his personality. Among other things, we learned that some of his favorite images were the ones he shot at California’s Manzanar Relocation Center, one of 10 U.S. internment camps where, from December 1942 to 1945 during World War II, more than 110,000 Japanese Americans were incarcerated.

On February 19, 1942, a little more than two months after the bombing of Pearl Harbor, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066, authorizing Japanese relocation. Manzanar opened about a month later, on March 21, 1942, as the Owens Valley Reception Center, and was later converted into a relocation camp. Designed to hold 10,000 people, it operated at, or near, capacity during the war.

“The residents worked in agriculture inside and outside the camp,” according to Military Museum. “The camp had its own farm area just to the south and a hog farm a half mile farther south. Guayule, a rubber-producing plant, was grown in several locations as part of a government-sponsored experimental program to grow natural rubber in the U.S. America's main supply of natural rubber had been lost when the Japanese invaded Southeast Asia. The camp also had a camouflage net factory, which was the only factory of any kind in any of the camps.

“Conditions at Manzanar were similar to those at the other camps, although Manzanar had a golf course where some of the other camps did not.”

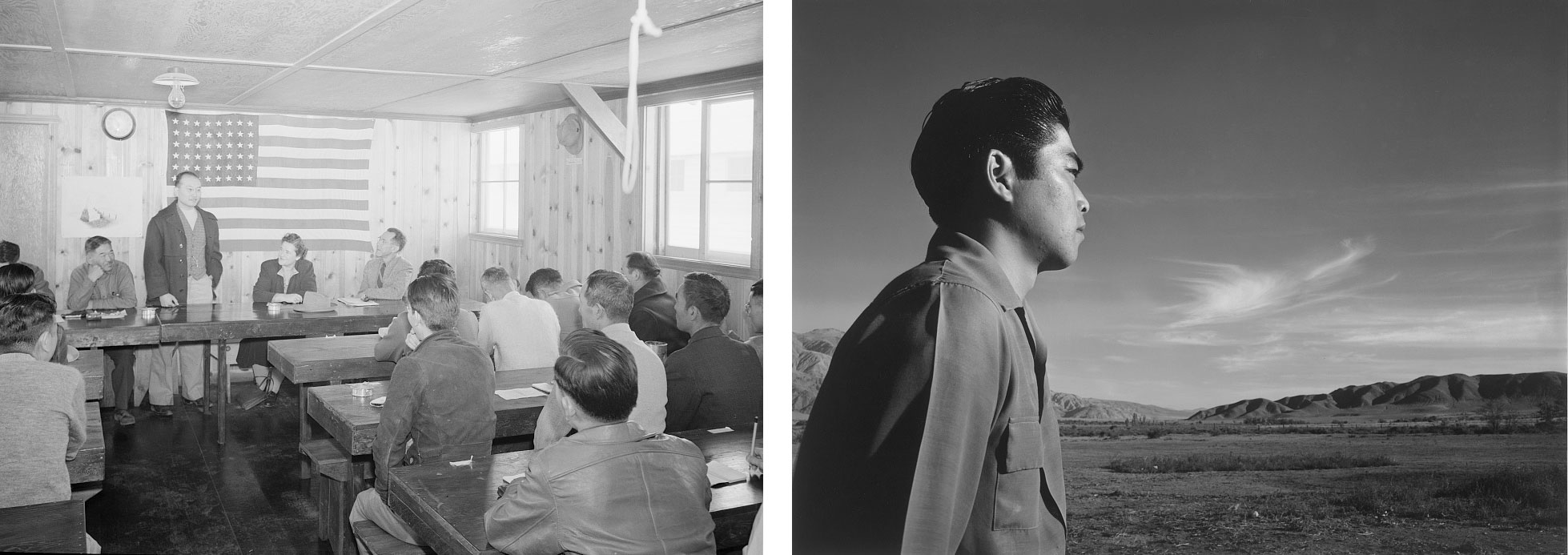

This was the scene that Ansel Adams encountered when he visited Manzanar in the fall of 1943. There he would take 240 photographs that would become one of the best records of the camp and some of the most well-known documentations of the internment era

Located in Inyo County about 200 miles northeast of Los Angeles, Manzanar sat in beautiful, if remote, country at the edge of the Sierra Nevada mountains. At the camp, Adams would shoot photographs that departed from his traditional landscape work. Concentrating on the internees and their activities, he produced portraits of the people and their family life — in the barracks; at work as welders, farmers, and garment makers; during recreation, playing baseball and volleyball.

A book of his images, called Born Free and Equal, was published in 1944. As Adams explained in a letter to a friend at the time: “Through the pictures the reader will be introduced to perhaps twenty individuals ... loyal American citizens who are anxious to get back into the stream of life and contribute to our victory.”

Apart from two images, Adams gifted his Manzanar photographs to the Library of Congress. The two he held back — both shots of the mountains near Manzanar in keeping with his famed landscape style — are among his most famous: Mount Williamson, the Sierra Nevada, from Manzanar, California, 1944; and Winter Sunrise, the Sierra Nevada, from Lone Pine, California, 1944.

After the last internee left the Manzanar Relocation Center on November 25, 1945, the camp closed. Manzanar was then dismantled, except for the camp auditorium, the only building that remains intact.

Now a national historical site, Manzanar is open to the public. Inside the Manzanar Visitor Center you’ll find exhibits, a 22-minute film, and a bookstore. In the camp itself, is Block 14, where you can see two reconstructed barracks, a women’s latrine, and a mess hall with exhibits. A 3.2-mile driving tour reveals remnants of orchards, 11 excavated rock gardens and ponds, building foundations, and the camp cemetery.

To see Manzanar as Ansel Adams did, you can view his photographs on the Library of Congress website. (The Library of Congress site also includes digital images of the first edition of Born Free and Equal.)

Offering the collection to the Library of Congress in 1965, Adams wrote in a letter, “The purpose of my work was to show how these people, suffering under a great injustice, and loss of property, businesses and professions, had overcome the sense of defeat and dispair [sic] by building for themselves a vital community in an arid (but magnificent) environment. ... All in all, I think this Manzanar Collection is an important historical document, and I trust it can be put to good use.”

See Collection Highlights here.