Talk about perfect casting: Bruce Dern, the living legend character actor who bushwhacked John Wayne in The Cowboys, tussled with James Garner in Support Your Local Sheriff, and dared to draw on Samuel L. Jackson in The Hateful Eight, will serve as host for Bruce Dern’s Cowboy Collection, a special selection of western movies that will air Monday through Sunday this week on the HDNET Movies cable channel.

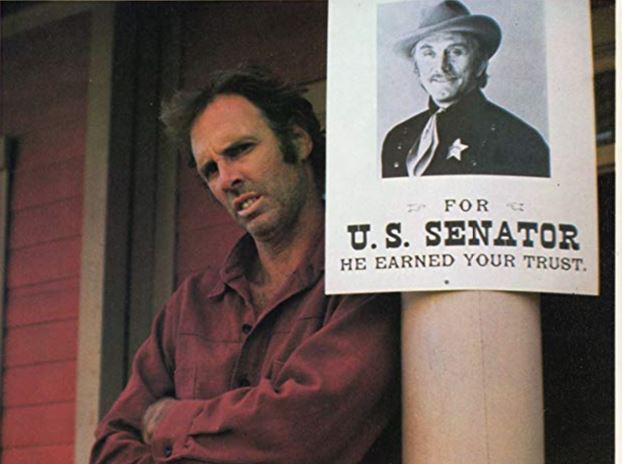

Chief among the lineup is an offbeat oater that's especially close to Dern’s heart: Posse, a brazenly cynical 1975 shoot-’em-up, at once deadly serious and savagely witty, about a celebrated Texas lawman who hopes to launch a winning campaign for the U.S. Senate, with a little help from his all-star posse, by capturing a notorious bandit. Kirk Douglas does double duty as director and star, and makes a memorable impression as Marshal Howard Nightingale, a preening hypocrite who travels with his very own publicity photographer. But as a filmmaker, Douglas generously cedes most of the script’s best lines to Dern, who gives a career-highlight performance as Jack Strawhorn, a cagey outlaw skilled at bringing out the worst in everyone.

“For me,” Dern said during a recent telephone interview, “the most appealing thing about it was the chemistry of the script, the mathematics of the script. I mean, you’ve got a good guy who turns out to be a bad guy, and you’ve got a bad guy who turns out to be another bad guy, but he tops the good guy because he’s not quite as bad.

“And Kirk Douglas was a real gentleman to me. He was a thorough professional — but he knew how to have fun. We had fun, all of us, the whole time we were making that movie.”

Of course, Posse wasn’t Dern’s first rodeo. In fact, eight years before he journeyed to Tucson for the on-location filming of that movie, he appeared, briefly, opposite Douglas and John Wayne in The War Wagon, a western directed by Burt Kennedy (who later cast Dern in Support Your Local Sheriff). Throughout the early years of his movie and TV career, he frequently got his cowboy on, more or less fulfilling the prediction of director and mentor Elia Kazan when Dern was a struggling New York stage actor.

“When I first went to Hollywood,” Dern said, “Mr. Kazan told me, ‘Just understand something: No one's ever going to know who you are until you’re in your 60s.’ I was 25 at the time. I said, ‘Why is that?’ He said, ‘Because you’re not a leading man. You’re not a conventional leading man, and you have a tendency to become the characters you play, which means there's no individual identity to you being the same person each time out. They like that. They like that people do have an identity. You're gonna go out there, and you're gonna be the fifth cowboy from the right for about 30 to 40 years. Just remember, be the most unique third cowboy from the right any goddamn person has ever seen.’”

Actually, Kazan was slightly off the mark in his prognosticating — Dern was 42 when he earned his first Oscar nomination, as Best Supporting Actor in 1978’s Coming Home — but never mind: Dern was ready, willing and able to accept that challenge. During his salad days in TV and movies, however, he dreaded those times when playing a cowboy meant actually spending time in the saddle.

“While I was growing up in Chicago,” Dern recalled with a chuckle, “I had to walk a long goddamn ways to even see a horse. So when I came out west, that's one thing I never did well — I never rode well. I rode with my life in my hands. I was terrified, and the horse knew I was terrified.”

With the passing of time, and his casting in several western films (Will Penny, Hang ‘Em High) and TV series (Gunsmoke, Stoney Burke, Wagon Train), Dern gradually overcame his phobia. But even after he no longer was a white-knuckle rider, he left certain things to the experts. During the filming of Posse, for example, he readily turned the reins over to veteran stunt man William H. Burton Jr. when potentially dangerous derring-do was required.

“There was one time,” Dern said, “when we were shooting near Florence, Arizona, which still had narrow gauge tracks so you could still run the old trains on them. We had quite a bit of stuff on the train, and that’s when Billy Burton, who doubled me, did the best stunt I’d ever seen done for me. He actually jumped a horse off a moving train. See, he had to be my character when a fire broke out in a boxcar, and I was supposed to have jumped on a horse, and jumped off a train — and went 140 yards down a cliff into a river. I was knocked out by what he did with that.”

Dern also cherishes fond memories of collaborating with Kirk Douglas, who pleasantly surprised him with an unexpected willingness, as director and co-star, to accept improvisation.

“There was the time I was in the jail cell on the train that they were using to transport me,” Dern said. “He comes up to me at my cell, and he’s smoking a big cigar. Now, up to this point, I hadn’t used any of what I call Dernsies — little things I put in from time to time, embellishments if you will, to enhance the character. And [Douglas] looked at me and, basically, he says, ‘I’ve got you now, and I’m gonna hang you,’ and so forth and so on. We’re talking back and forth, and then he says, ‘And after that, I'm gonna become the governor of the territory,’ and this and that. So than, I said, ‘And after that, is it gonna be the big one?’ He looked at me, and stopped. Looked at the camera. Then he looked at me again and said, ‘That’s the best line I’ve ever heard in a situation like this. That's not in the script.’ I said, ‘You’ll get one every now and then. I just can't resist the urge to put something in, if you don’t mind.’ He said, ‘No, you shouldn’t resist. You should do that all the time, because it’s quite creative and inventive, and fits the character perfectly.’”

Dern laughed at the memory.

“So that,” he said, “was my first big star okaying the fact that I could interject something now and then, to get a point across.”