Before they produced license plates, inmates in the West served some artistic time making hitched horsehair bridles.

The flowing mane and tail of the horse have been used for many purposes, both utilitarian and aesthetic, ever since humans paired up with equines. The strong, waterproof, dye-able strands of hair became a component in the creation of ropes, girths, and war bridles for horses. Horsehair was also used for fishing line, stuffing for mattresses and furniture, and decorative additions to clothing. It is still used on bows to draw notes from stringed instruments.

Yet the hitching of horsehair in the construction of bridles is a unique American folk art. In no other culture has horsehair been used in quite this manner. In making bridles, the long hairs of the horse’s tail were the most useful, and when dyed brilliant colors, they could be braided or hitched into beautiful pieces: belts, hatbands, watch fobs, canes, quirts, and bridles with reins.

Over the years, many people have mistakenly assumed that these beautiful antique horsehair pieces were made by Native Americans, who were known to have used horsehair to make ropes, war bridles, and some headstalls. However, among Native Americans, the more common and efficient techniques of twisting and braiding were most often employed, rather than hitching. Most Indian horsehair work was done with the natural colors of horsehair and plant-based dyes. They also used horsehair decoratively, tying strands to embellish their clothing or their hair.

We now know that many of the hitched horsehair bridles extant today were created by the inmates of the West’s territorial and state penitentiaries. Since it was believed that inmates who were busy and productive had fewer problems and caused less trouble, some wardens promoted hobby programs. The prison warden usually determined the types of activities available for inmates, depending on security levels and what raw materials and tools could be used.

The craft of hitching horsehair into colorful bridles flourished in the prisons of 12 western states from about 1885 through the 1920s. (One wonders if the term “doing a hitch” was related to this inmate activity.) Horses were always kept on the prison farms, so most of the required materials were inexpensive and readily available. Hitched and braided horsehair pieces were created by hand without the benefit of any special tools and could be made in the confines of a small cell. The inmates had the time to devote to this folk art, which required focus and attention to detail for long periods.

By producing pieces that would sell “on the outside” for a good price, inmates could earn money for tobacco or to save for their release. One hundred years ago, these bridles would sell for $20 to $50 each. The prisoner might get two-thirds of that, while the remainder would go to the prison for supplies. Besides the monetary return, inmates gained a sense of pride in producing useful, artistically satisfying objects valued by others.

Some speculate that Mexican prisoners brought the craft of horsehair hitching to the prisons of the far West and taught other inmates. But there are very few early horsehair bridles found in Mexico. It is possible that Spanish sailors, who were experts at knotting, first brought this skill to the New World in the 16th century. Many of them stayed in Mexico and passed on their techniques to others, some of whom might have ended up in prison, where they passed the time tying knots and using whatever fiber was handy.

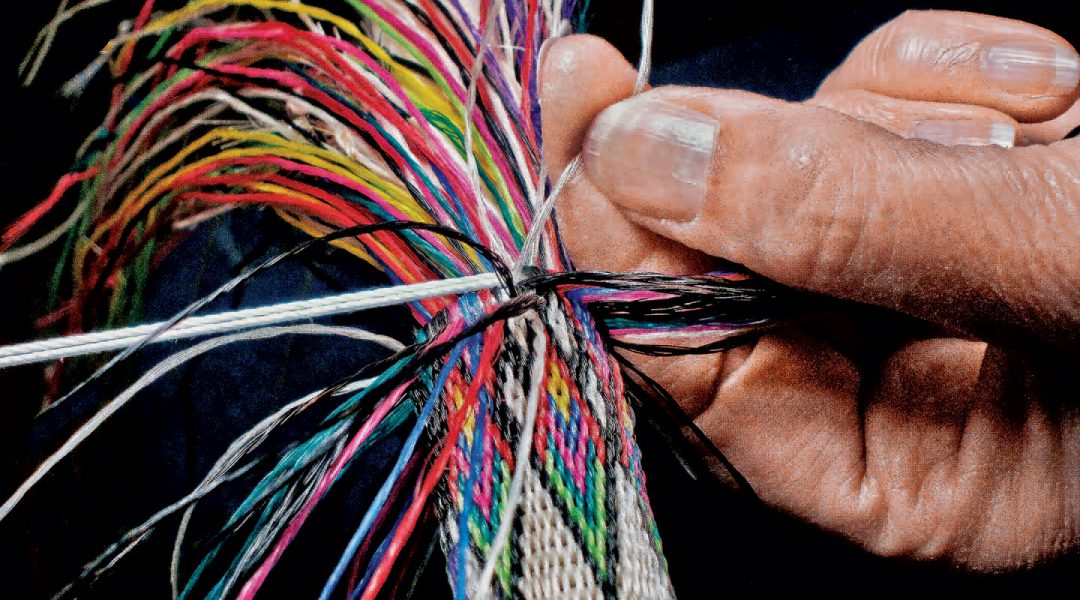

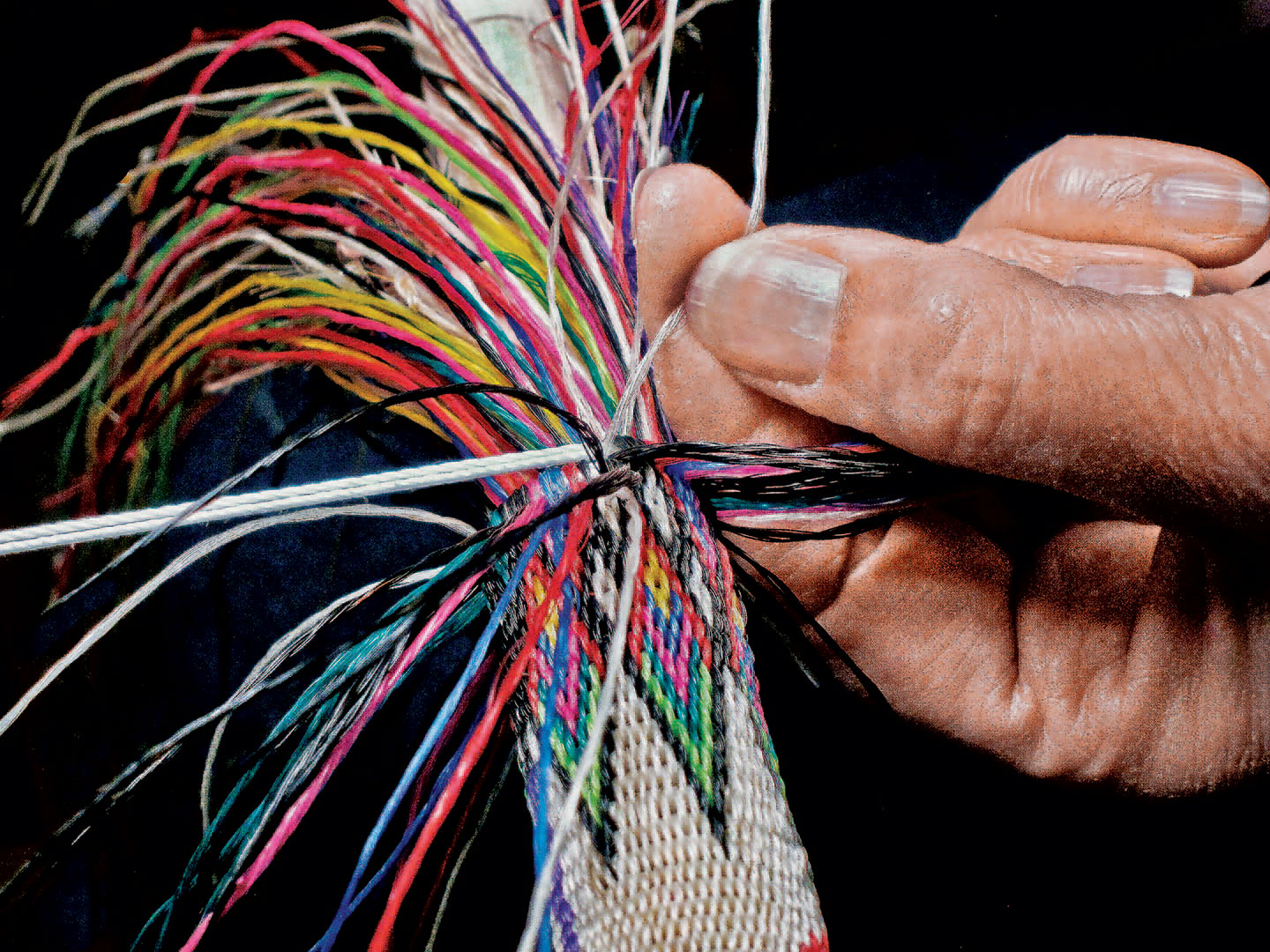

In hitching, a series of horsehair pulls, or strands, is knotted over string that is wound around a wooden dowel. The dowel provides something sturdy to hitch over and provides shape for the item to be hitched — usually in geometric patterns based on a diamond shape.

Bridles took the longest time to produce. An inmate might work on a relatively simple braided headstall for about six weeks, while an elaborate, colorful hitched bridle might take four to six months to complete. Such a piece would require 40,000 half-hitch knots.

Each of the Western prisons had its own style of bridle with particular colors and patterns in the horsehair, along with different styles of tassels and rosettes. Inmates at Arizona’s Florence State Prison — completed in 1908 to replace the territorial prison in Yuma — made the most original bridles, which employed bright colors and different types of knots. At Montana’s territorial prison in Deer Lodge, inmates put text or numbers on bridles. Wyoming prisoners utilized a combination of braided calfskin and hitched horsehair. Cañon City, Colorado, inmates braided their bridles and made their own bits.

The earliest bridles, especially those made at Yuma Territorial Prison, were crafted of horsehair in its natural colors: black, white, and brown with only small color accents. Through the years, black and white alone were usually only seen on bridles crafted at Deer Lodge, Cañon City, or Laramie, Wyoming. It is interesting to note that bridles made from 1911 to the 1930s incorporated red, orange, blue, turquoise, yellow, pink, and purple, and they had more creative color combinations and patterns than the pieces made before or after that time. Bridles made since the 1970s tend to be narrower with fewer tassels, and often feature leather buckles for bridle adjustments and for connecting the headstall to the bit. The rosettes are made by the inmates out of leather and silver rather than the glass preferred by manufacturers.

Today the tradition is kept alive by the inmates of Montana State Prison, whose horsehair bridles are for sale in the prison outlet store in Deer Lodge.

At the Inmate Hobby Store

An inmate talks about the historical and contemporary prison pastime of horsehair hitching.

Across from the old territorial prison in downtown Deer Lodge, Montana, inmate hobby clerk William Hart is at work manning the Montana State Prison Hobby Store. Among the many items he rings up for customers who stop in on historic tours of the prison buildings are hitched horsehair bridles, which have been crafted by inmates here for almost 150 years.

“Horsehair hitching as a hobby in the prison here dates back to the 1880s. I’ve personally had my hands in the hair, so to speak, for several years,” says Hart, who learned the craft from another inmate. “There aren’t any organized classes. It’s all self-taught, refined, and passed on.”

The inmates buy their own supplies and pay their own shipping. When they sell a piece in the store — there’s currently no way to sell online — 75 percent goes to the inmate-artisan and 25 percent to the store to pay store overhead. “Before that money becomes spendable,” Hart explains, “a portion is taken out for anything the inmate might owe, like, for instance, child support. What money comes back to them, they might use it for phone time, stationery, commissary, pop and candy, sending money home, and saving up for release.”

Today, the best examples of horsehair bridles might sell at the prison outlet for $1,500 to $5,000 and more. Beyond the income potential, there’s pride of craftsmanship. For Hart, a particular piece comes to mind. “The piece I’m proudest of is a bridle that came down here to the store. It was all horsehair. It’s very meticulous work; you have to make sure that each knot and each hitch is exactly where it’s supposed to be. On the flatwork alone, there’s anywhere from 800 to 1,200 hitches. It takes about two hours an inch for flatwork, which doesn’t include needleknotwork or the assembly itself. This bridle was all diamond patterns and had hitchwork on the inside of the piece so that it hung nicely and displayed well.”

Hart is one of nearly 300 inmates who hitch horsehair and sell their artistry in the store. It’s more a hobby than a living.

“First, you have to have a job [in the prison] to have the money to buy the supplies,” Hart says. “To give you an idea, one piece that took a year to make and sold for $3,400, easily had $400 of wholesale horsehair in it. And you can’t use all of the horsehair you buy because you have to pick out the brittle and other unsuitable strands. With all that goes into it, you don’t really make all that much. Then vendors will come here and buy these pieces and resell them at big venues for lots more. They can easily double their money.”

In spite of that, Hart says, the hobby program is well-received and he feels lucky to have it. “Making these horsehair bridles requires intense concentration. It’s a good pastime for penal institutions because of the rehabilitative aspect and because it allows you to escape your situation. You get so focused that it becomes a mental escape from the incarcerated environment you find yourself in.”

— Dana Joseph

Jody and Ned Martin are the authors of Horsehair Bridles, A Unique American Folk Art (2015, Hawk Hill Press).

From the April 2016 issue.