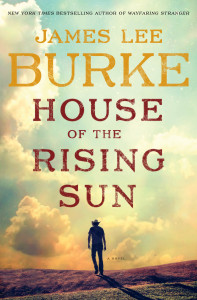

To bestselling western writer James Lee Burke, every story is a grail quest. His latest, House of the Rising Sun, drives the point home.

Every story in Western literature is a quest for the Holy Grail, and those quests began before the mythical relic even existed. The pursuit of life and redemption is at the center of pre-Christian mythology, of pioneer narratives, Wild West tales, and Beatniks’ amphetamine-fueled cross-country road trips.

At least, that’s the way western writer James Lee Burke sees it. His latest novel, House of the Rising Sun, is just a bit more literal about it than most.

“It’s a story of the search for the Grail,” he says. “You see, this is my view of Western occidental art: All of it is about the search for the Holy Grail. Jessie Weston [said so] in her book, From Ritual to Romance. One of the greatest books ever written is probably The Golden Bough by James Frazer. And both those authors said that the Arthurian legend is one that defines Western civilization.”

Burke ties this idea to Celtic legends about horsemen riding across the sky in pursuit of a stag, to the pagan story of the life-giving bowl of Brigid, and even to the westward rambles in Jack Kerouac’s On the Road.

“It’s built into our unconscious, particularly in this country,” he says. “The West has always been our secular cathedral. Always. Anyone who does not love the western United States is spiritually dead, in my opinion. It’s a glorious place.”

House of the Rising Sun is one of Burke’s Holland family tales, drawing inspiration from Burke’s own ancestors. It follows Hackberry Holland, a retired and battle-weary Texas Ranger, as he searches for his estranged son Ishmael, an army captain seriously wounded (in both senses of the word) by his own war experiences. Hackberry also happens to be in possession of what may be the legendary Cup of Christ, which he salvaged from a weapons-filled hearse shortly before setting the vehicle ablaze in the aftermath of a deadly run-in with corrupt Mexican soldiers. Unfortunately for Hackberry, the hearse belonged to a ruthless Austrian arms dealer who plots to leverage Ishmael in his bid to get the relic back.

House of the Rising Sun is one of Burke’s Holland family tales, drawing inspiration from Burke’s own ancestors. It follows Hackberry Holland, a retired and battle-weary Texas Ranger, as he searches for his estranged son Ishmael, an army captain seriously wounded (in both senses of the word) by his own war experiences. Hackberry also happens to be in possession of what may be the legendary Cup of Christ, which he salvaged from a weapons-filled hearse shortly before setting the vehicle ablaze in the aftermath of a deadly run-in with corrupt Mexican soldiers. Unfortunately for Hackberry, the hearse belonged to a ruthless Austrian arms dealer who plots to leverage Ishmael in his bid to get the relic back.

The story is largely set in the early 20th century, decades after the era usually depicted in western movies, TV series, and novels. But just as we have modern-day westerns, Burke believes the rugged, independent spirit of the West is still very much alive. In fact, he says, that is the true spirit of this country.

“That’s where the American ethos comes from,” he says. “We’ve got it backward. We always think in terms of the inception of the nation taking place in Philadelphia and Boston. Not true. It’s the other way around, up into contemporary times. ... The American dynamic is based on the ethos of the American cowboy. He’s the existentialist hero. And the American film industry is predicated on that hero.”

Burke’s heroes haven’t always been cowboys, though. His 35 other published works include short story collections, small-town crime thrillers, and perhaps his best-known work, a series of Louisiana-set novels starring detective Dave Robicheaux. Two of the Robicheaux mysteries, Heaven’s Prisoners and In the Electric Mist With Confederate Dead, have been adapted to film. Heaven’s Prisoners (1996) starred Alec Baldwin but was not a hit with moviegoers or critics. The latter book was source material for the 2009 Tommy Lee Jones vehicle In the Electric Mist, which was released overseas to a positive critical reception but has only been widely released in the United States on DVD (in a shortened edit) and online. And the Texas Revolution-set Two for Texas was turned into a 1998 TV movie starring Kris Kristofferson.

Burke doesn’t seem bothered by the lackluster response to the film adaptations of his stories. He calls visiting the sets “great fun,” but he stays out of the way, with the attitude that once he’s turned something over, it’s out of his hands.

What remains in his capable hands is the ability to create flawed, believable characters; weave intricate, compelling plots; and craft authentic, genuine dialogue. More than 50 years after the publication of his first novel and some 60 years after his first short story was published, he has no plans to retire. He offers up a bit of wisdom a Franciscan theologian once told him: “ ‘In your life and in your work, you make a choice between good and evil. And once you choose good over evil, you stop taking score.’ ... You never plan, you just do it a day at a time for the love of your art and try to make the world a better place if you can.”

From the January 2016 issue.

Photography: Courtesy James McDavid