Drawn to stoicism in the midst of savagery and the calm within the storm, this photographer has found the perfect subject — cowboy life In Colorado.

Michael Crouser grew up in a peaceful tree-lined Minneapolis suburb — a childhood lifted straight out of a John Cheever novel — and attended college at Saint John’s University, a Catholic all-boys school in central Minnesota. His speech is soft and measured; his smile is shy. It could come as a surprise, then, that the photographer launched his artistic career by traveling to distant corners of the world, snapping black-and-white pictures that often brimmed with violent physicality.

For his book Los Toros (Twin Palms Publishers, 2007), Crouser spent 15 years visiting the bullrings of Spain, Mexico, Ecuador, and France, capturing the provoked animals as they charged stoic matadors; it was awarded first prize for Fine Art Book at the 2008 International Photography Awards. For his book Dog Run (Viking Studio, 2008), he shot everything from canines happily at play in urban parks to gritty scenes of lop-eared mutts baring their teeth at passing pit bulls. But while his subject matter can verge on the savage, the works themselves are subdued and graceful. The lines are gentle; the light diffused. It’s an aesthetic, Crouser says, that reflects his own personality.

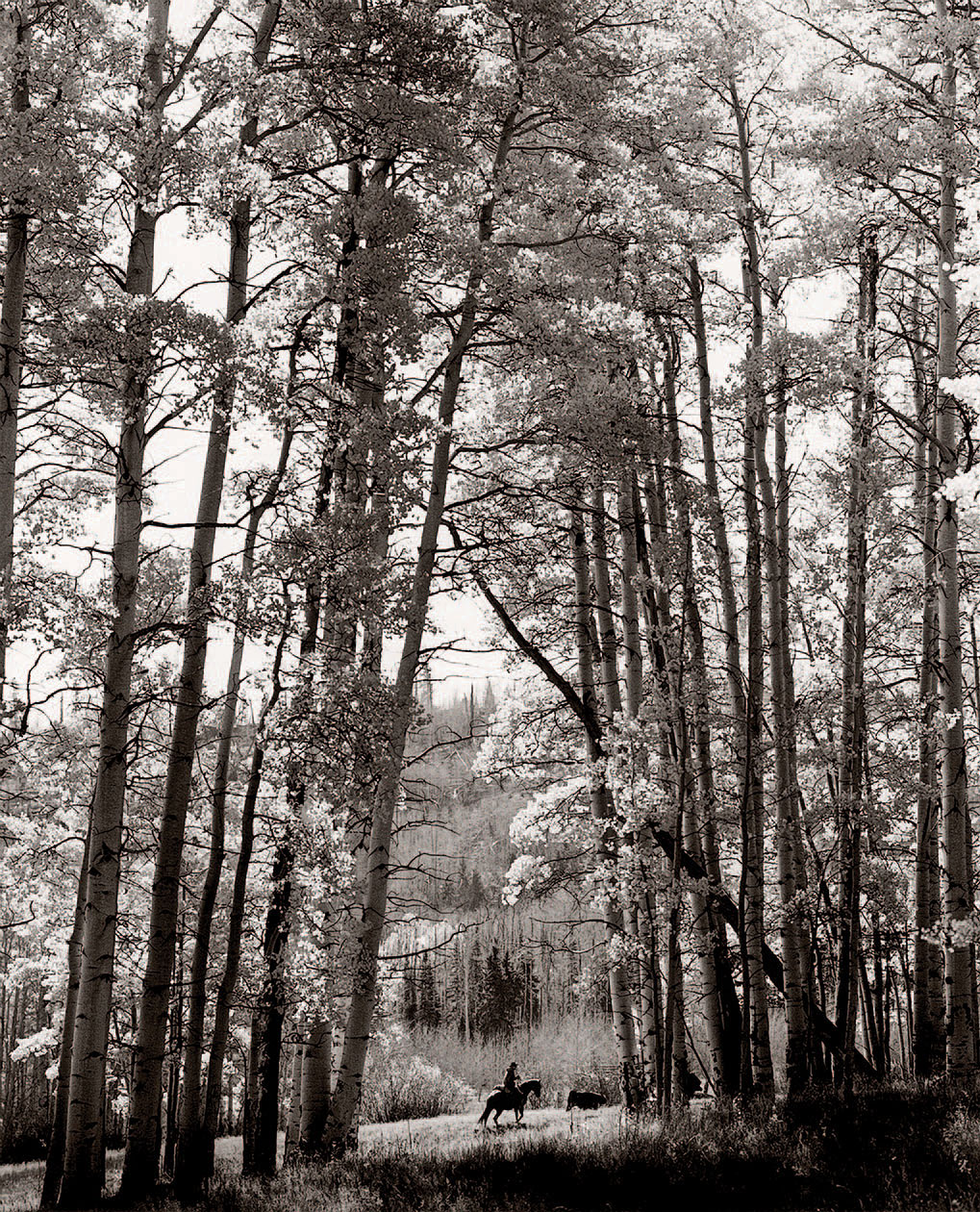

“I shoot tranquil pictures of intense moments,” he says. “I think there’s something to the softness, something to the composition, something to the presentation and the editing. I tend to be a person that comes off as pretty calm and steady. And yet beneath the surface, there’s a lot of turbulence going on. It comes out in the pictures. There’s sereneness in the flow of movement. There’s a calm within the storm.”

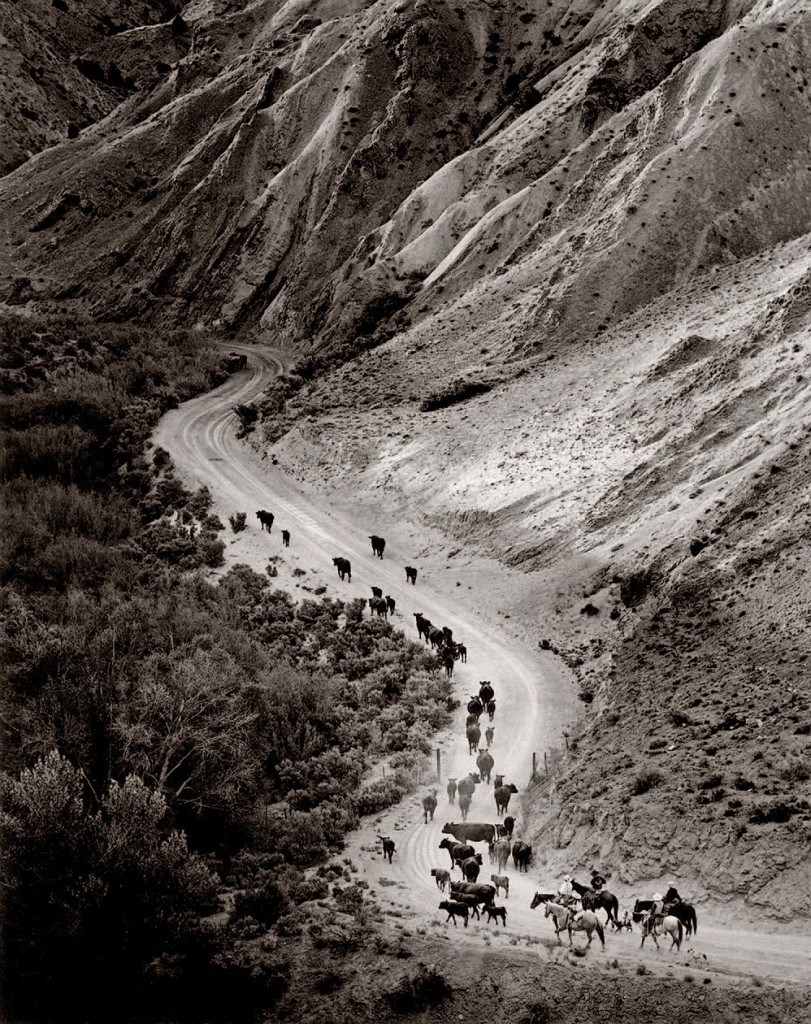

For his latest long-term project, Crouser shifted his attention to a series of small mountain ranches in rural Colorado, where he has spent the past eight years photographing the cowboys who work the land, run the cattle, and maintain a time-honored Western way of life — even as modernization and urban development threaten to erase their future existence. He calls the series Mountain Ranch and plans to eventually compile the images into a monograph.

Crouser chose to focus on cowboys because he’s interested in their work. “I find it far more fascinating, sociologically and photographically, than I do city life,” he says. “I’m interested in disappearing cultures; I’m interested in rougher ways of life. I’m interested in animals, in living outside. I’m interested in dirt and blood and sweat.”

Crouser’s documentary-style shots vacillate between poetic and graphic, whimsical and wild. In one photograph, a horse grazes beneath a flowering tree. In another, a group of men pin a calf to the ground, branding its flesh with a sizzling iron. In yet another, a cowboy climbs a wooden fence to steal a kiss from a woman standing in the pasture on the other side. Taken together, they form a narrative of the daily activities that give structure and rhythm to the ranchers’ lives.

There’s a timelessness here, in both the appearance of the ranchers and the richly warm black-and-white photographs themselves. There’s no farming machinery or apparel to date the subjects or images to a specific era. The moments Crouser portrays could have occurred as easily in 1814 as in 2014. This effect is deliberate, echoing, he says, a personal photographic philosophy called sin tiempo, a Spanish phrase that means “without time.”

“I’m not really interested in cowboys in sunglasses and baseball hats,” Crouser says. “The dress is really important to me. Most of the people I photograph dress in a traditional way. They do that because, one, it’s practical, but, two, it’s what they come from. The phrase they use is ‘the real deal.’ When you pay attention to that aesthetic over the course of a series, it leaves an impression on the viewer of a place, a subculture without time. That doesn’t mean that these people don’t ever get on a four-wheeler or wear tennis shoes. They do. But I’m not interested in that element of their lives.”

Crouser cautions, however, that Mountain Ranch shouldn’t be viewed as a lament. There’s no political statement behind the series. It’s not intended to mourn a vanishing community or to create a visual juxtaposition of the modern cowboy and the archaic ways of the rural rugged rancher. “I’m trying to just make rich and true photographs,” he says.

As for what’s next, Crouser is starting to wrap up Mountain Ranch after spending nearly a decade amid the cattle-dotted foothills of Colorado in preparation for taking on a fresh subject. But he’s in no particular hurry. “The [cowboys’] way of life is something that fascinates me as much now as it did when I started.”

Michael Crouser is represented by Verve Gallery of Photography in Santa Fe, Corden-Potts Gallery in San Francisco, and ClampArt in New York.

From the February/March 2015 issue.