The idea was ludicrous, but simple: to crash two trains. The result? Explosive beyond belief.

It’s 1896 in Texas.

The Lone Star State is transitioning from the no man’s land of the Wild West to a more sophisticated and stable economic wonderland. Disappearing are the hardened cowboys and greedy bandits, making way for prosperous cattle ranchers and mechanically savvy industrialists.

It’s the perfect market for the country’s most burgeoning business: railroads.

Enter William George Crush, an up-and-comer at the Missouri, Kansas and Texas Railway Company — popularly called the Katy — who decides to make a name for himself by proposing one of the most ludicrous ideas in railroad history.

Even more ridiculous: His bosses say yes.

The Idea

Fancying himself the next P.T. Barnum, the ever-imaginative Crush draws on the country’s rubbernecking fascination with train wrecks — which have become increasingly commonplace since the dawn of railroads in the United States more than 50 years earlier — to mastermind a publicity stunt unlike any other.

He envisions a staged train collision between two 30-ton steam engines, barreling toward each other at nearly 50 mph and meeting in a glorious explosion of fire and sparks. Crush suggests that the Katy railroad company invite all Texans to witness the historic event.

In a stroke of marketing genius, Crush decides that rather than a typical entrance fee, the occasion itself will be free. The lone cost, a $2 fare from anywhere in the region.

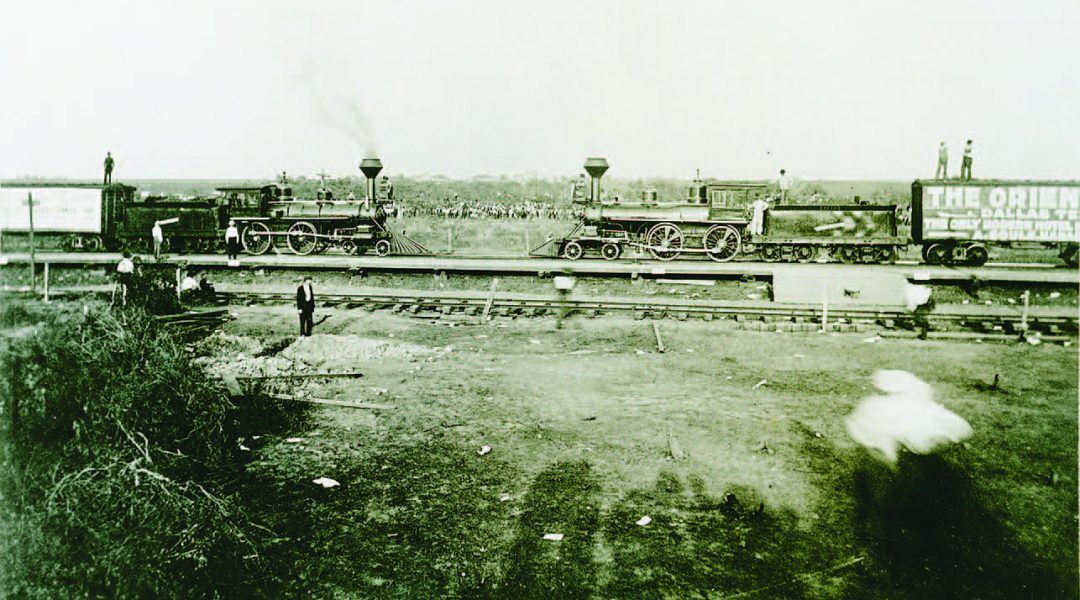

With approval from the Katy brass, Crush picks the date of September 15, 1896. He selects a pair of decommissioned 20-year-old engines: Old No. 999, painted green with red trim, and No. 1001, painted red and trimmed in green.

And he chooses the site, a shallow, vacant valley just north of Waco, in what is now McLennan County. He calls it — what else — Crush, Texas.

Crush spends the summer prior to the event on a widespread publicity blitz, touting the big day as the must-see social event of the century. He tours the steam engines across Texas, proudly displaying them for looky-loos and passersby. The Katy prints bulletins and handbills, and buys ad space in circulars to publicize the event.

The City

Throughout the summer, talk of the “Crash at Crush” is so popular that local and regional newspapers run daily reports on the preparations and progress. By the time tickets become available, the Katy offices are flooded with requests.

So Crush and the Katy begin creating the temporary city.

They build a one-of-a-kind train depot, a massive grandstand, two telegraph offices, a press box, and a bandstand for live music.

They install three speaker podiums for the ever-growing line of politicians from across the state eager for a chance to speak to a captive throng of potential voters.

They erect a carnival midway with an array of medicine shows, games, and lemonade stands for families with children. Crush borrows a Ringling Bros. circus tent to house a makeshift restaurant. A jail is built for misbehavers and ne’er-do-wells, and more than 200 constables from around the region are hired to enforce the law.

But the centerpiece is a shiny, new sign that graces the train platform, informing passengers that they have, in fact, arrived — at Crush, Texas.

The Big Day

Due to the hype, Crush expects a healthy crowd of close to 20,000, and the Katy brass agree that anything close to that number of attendees would be a rousing success. But for once, Crush has underestimated himself.

By afternoon, dozens of jampacked passenger trains deliver nearly 50,000 people to the grounds. The trains are so crowded that some passengers are forced to ride atop the cars because there is no room inside.

While the massive crowd enjoys the pageantry, Crush and the rest of the Katy crew spend hours checking over their trains. They conduct speed, mechanical, engineering, and safety analyses on each of the steam engines.

After lengthy testing, Crush is assured by engineers that even under the most high-speed circumstance, an explosion of any dangerous size is nearly impossible. Even so, Crush asks the constables to keep the 50,000 anxious spectators approximately 200 yards away from the track.

Lucky for them.

The Crash

Once the crowd is in the designated safe zone, Crush appears in flamboyant fashion, riding a white horse. He addresses the crowd, raising a white hat and pausing for dramatic effect before hurling it down to the ground to signal the start of the main event.

With that, the locomotives begin hurtling madly toward each other. They spew black smoke and whistle steam as the throttles are thrown wide open. At dangerous speeds, the engineers and other crew jump from the trains as planned and roll safely away.

The trains come roaring into sight of the crowd at more than 50 mph. According to a report a day later in The Dallas Morning News, “The rumble of the two trains, faint and far off at first, but growing nearer and more distinct with each fleeting second, was like the gathering force of a cyclone. Nearer and nearer they came, the whistles of each blowing repeatedly and the torpedoes which had been placed on the track exploding in almost a continuous round like the rattle of musketry.”

People in the crowd shove their way closer to the anticipated collision, climbing nearby trees and scaling each other’s shoulders to get the best possible view. Nearer and nearer the trains come. One minute passes. Then another. And another.

Finally the trains meet.

A deafening, ear-splitting snarl fills the prairie as the two machines rip into each other. The six cars being pulled by the steam engines piggyback and telescope into one another, creating a metallic tower of boxcars.

A shower of molten steel and flowing smoke erupts as boilers on both locomotives detonate like bombs. The sky is suddenly filled with flying shrapnel, the odd-shaped projectiles piercing through the crowd. There are sprays of blood. Clouds of dust and dirt and wood. Screams of panic. In an instant, chaos rings through the trampled field and the previously jovial crowd turns hysterical.

The Aftermath

Three people are killed almost instantly. Dozens more are injured. But in the chaos and mass exodus, it’s unknown just how many were truly affected by the catastrophe.

The Katy sends in freight trains to remove the bulky wreckage, and souvenir hounds take care of the rest. The city, which for a few hours was one of the largest in Texas, disappears by nightfall.

So too, of course, does Crush himself. He is fired on the spot.

But as news spreads and the days pass, the Katy railroad company begins to see that the event accomplished its goal. The “Crash at Crush” makes headlines around the world for weeks, and the company’s business picks up speedily. The Katy is the most talked about rail line in America. It pays all claims to those injured and the families of those killed, offering cash and lifetime rail passes.

As for Crush, he’s rehired the morning after the event and remains a stalwart with the Katy until his retirement, with 57 years of service at the railroad.

From the August/September 2014 issue.